British Airways, easyJet and other major carriers say that by supporting forest conservation they can offset emissions. A new investigation shows the bold claims can’t be verified

Britaldo Silveira Soares Filho was on a boat on Brazil’s Rio Negro river the first time he was asked to help rubber-stamp a carbon offsetting project.

The deforestation modelling expert spent three days aboard in 2007 along with other Amazon rainforest specialists tasked by a Brazilian NGO with checking the science behind a forest conservation programme.

Back in his office in São Paulo, he concluded that he didn’t want his world-leading software to be used for the project or others like it.

“It’s a scam,” he said. “Neither planting trees nor avoiding deforestation will make a flight carbon neutral.”

But airlines are still backing offsetting schemes to help them hit climate targets.

The aviation sector has pledged to halve emissions by 2050, while increasing passenger numbers. Yet non-polluting aircraft fuels are still a long way off. Instead, airlines are turning to offsetting to reduce climate damage, buying credits credits from projects that promise to preserve forests.

“It’s a scam. Neither planting trees nor avoiding deforestation will make a flight carbon neutral.”

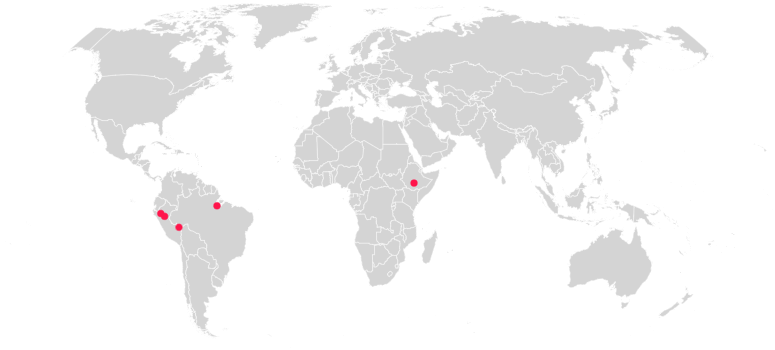

Last year, British Airways told passengers they could “fly carbon neutral” by buying forest protection credits. EasyJet uses offsetting projects in Peru and Ethiopia to “become a more carbon neutral airline” and Delta, one of the world’s biggest carriers, uses them to support its aim to become the “first carbon neutral airline globally”. Air France, Iberia, Qantas and United Airlines all use similar programmes.

An investigation into how these schemes calculate their carbon savings by SourceMaterial, with Unearthed and the Guardian, raises serious doubts about their ability to match major airlines’ claims.

SourceMaterial examined 10 reduced deforestation offsetting projects used by major airlines and certified by Verra, the biggest issuer of carbon credits. Satellite analysis, documents, interviews and on-the-ground reporting revealed that while they can provide some benefits to the environment and local communities, their attempts to quantify and market carbon offsets are based on shaky foundations.

‘Pure public relations’

Avoided deforestation schemes generate and sell carbon credits based on the amount of tree felling they claim to prevent. To work out these carbon savings, they predict how much deforestation would take place if the project didn’t exist.

Satellite analysis of tree cover loss in the projects’ reference regions, carried out by consultancy McKenzie Intelligence Services, found no evidence of deforestation in line with what had been predicted by the schemes.

Analysis of schemes backed by British Airways, easyJet and United suggested that the scale of the carbon benefits they offer is impossible to verify. One of the projects is run by two logging companies that cut down ancient and rare trees.

“It’s a scandalous situation,” Philip Fearnside, an ecologist at the National Institute for Research in Amazonia, said of the current state of the REDD+ system. “Most of this is pure public relations.”

The findings come as the carbon offset market is reaches a crucial point. The UK finance minister, Rishi Sunak, is aiming to make London the global hub for the trade of voluntary carbon offsets and former Bank of England governor Mark Carney is leading a task force to expand the market.

“It’s a scandalous situation. Most of this is pure public relations.”

They also come as Verra, the largest issuer of avoided deforestation credits, is overhauling its methodologies to help the market scale-up and following repeated media stories about the validity of the credits it produces.

In a statement, Verra said that SourceMaterial, Unearthed and the Guardian did not understand how its methodologies work, that the investigation was “fatally flawed”, had not produced fact-based journalism, and ignored Verra’s success in preserving forests.

‘No impact‘

Protecting forests is crucial if the world is to avoid catastrophic climate change and carbon offsets are intended to offer a mechanism to achieve this.

Since at least 2005, the UN has been discussing the idea of paying to protect forests. The idea was formalised in a collection of policies known as Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Degradation (REDD), later REDD+, to fund conservation projects in developing countries, with the goal of mitigating climate change. The first REDD+ project began issuing carbon credits in 2011.

There is no central body to regulate these projects and carbon offset markets, allowing private companies to carve a niche issuing credits and certifying standards. Verra, which certified of all the projects in this investigation, has approved nearly 1,700 around the globe.

A project goes through a series of checks before certification to show that it will help conserve an area facing a real threat of deforestation. Crucially, it needs to demonstrate “additionality”—evidence that the trees would be lost if it did not exist.

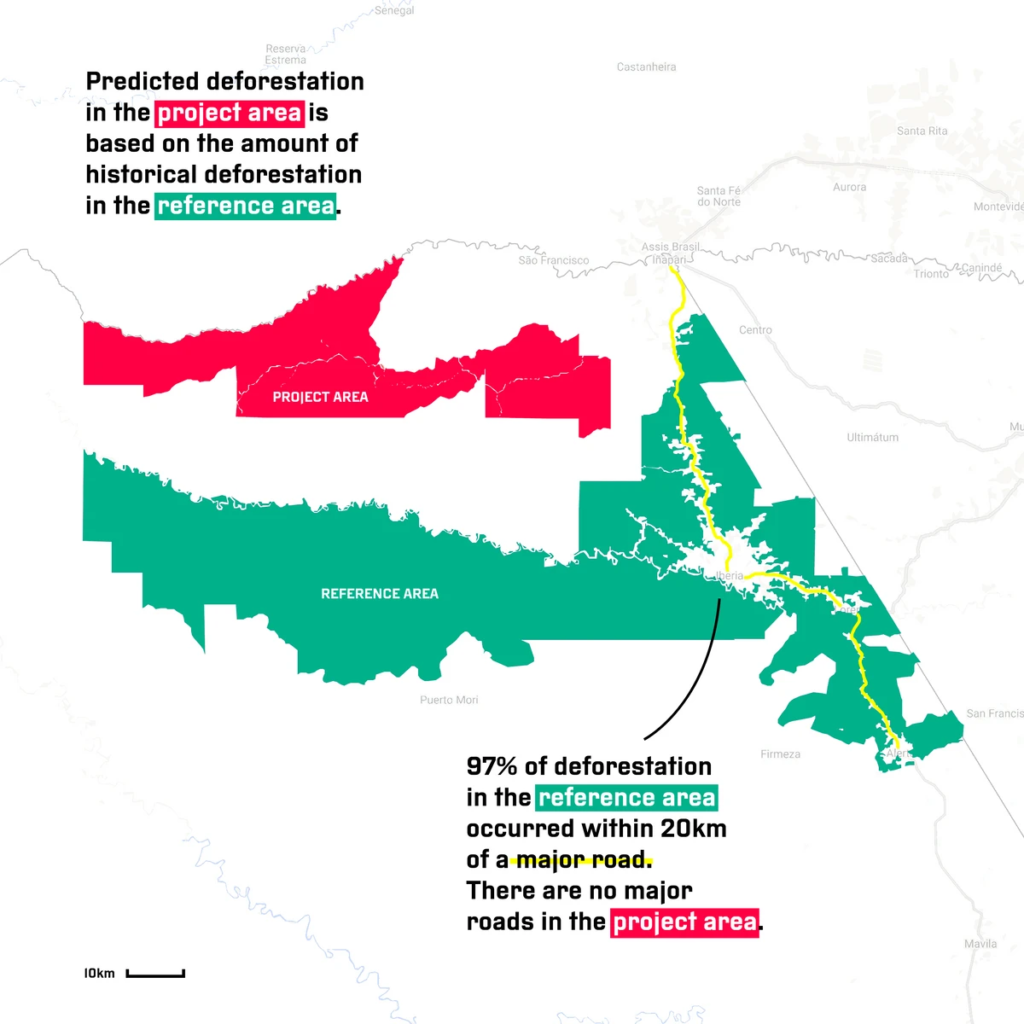

Developers calculate additionality using a baseline scenario, a hypothetical estimation of how many trees would otherwise be lost. This normally taken from a “reference region” of nearby forest facing a comparable threat.

But at an offsetting initiative supported by easyJet in a remote area of forest in the Madre de Dios region in Peru, the reference region is a much more heavily populated area close to a major road, where deforestation is naturally higher. Trees there are less likely to be cut down, throwing doubt on the initiative’s claims to have saved forest in the project area.

Verra rejects this criticism. It says it is adapting its methods, using national and local deforestation data rather than reference regions, and reviewing deforestation every four to six years.

But gaps remain, experts say. Projects can issue credits even as overall deforestation in the country continues to rise, and there is no guarantee trees will not be cut down after projects—sometimes scheduled to last 20 years—end.

Most importantly, there remains no way of verifying if projects’ claims for their impact, based on historical models, are accurate in the real world, said Alexandra Morel, an ecosystem scientist at the University of Dundee.

“It’s impossible to prove a counterfactual,” she said. “Rather than just valuing what forests are actually there, which are actively providing a carbon sink or store right now, we have to surmise which forests would still be here versus which ones are the bonus forests that were spared from the theoretical axe. It is so abstract.”

Thales West, a scientist at the New Zealand Forest Research Institute who worked for five years as an auditor of REDD+ projects, said that Verra’s methodologies “not robust enough”.

“There is room for projects to generate credits that have no impact on the climate whatsoever,” he said.

“It’s impossible to prove a counterfactual”

West led a September 2020 study examining 12 projects avoided deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon.

“We find no significant evidence that voluntary REDD+ projects in the Brazilian Amazon have mitigated forest loss,” the paper concluded.

At one of the projects, Floresta de Portel in Pará in northern Brazil, used by Air France to offset emissions, scientists found deforestation levels similar to those at an unprotected area nearby.

An Air France spokesperson said carbon offsetting is “part of a larger scheme” to address emissions. Michael Greene, a spokesperson for the Floresta de Portel project, said the project had acted as a bulwark against the impacts of illegal loggers and cattle ranchers.

Modelling carbon savings

To predict deforestation, Verra projects often use software called Dinamica EGO. It was never intended for use by REDD+.

“We do not support the application of deforestation modelling to fix REDD baselines for crediting purposes,” Dinamica’s website says.

Instead, Dinamica was created to monitor the potential impact of policy decisions, said Soares Filho, the Sao Paolo forest expert, who designed it. In 2006, for example, he and his colleagues used it to model the expansion of the cattle and soy industries in the Amazon basin. What the software can’t do, he said, is definitively estimate future forest loss in a given area.

“Models are used to avert an undesirable future, not predict the future,” he said. “Models are not crystal balls.”

In response to question from SourceMaterial, Farm Africa, a charity that manages one of the projects backed by easyJet that used Dinamica EGO, said: “We remain confident that the deforestation scenarios the model produced are the best that science could provide at that time.”

Airlines are using offsetting as an excuse to avoid more meaningful emissions reductions, Soares Filho said.

“It would be more efficient investing in research on more efficient jets or alternative fuels, for example,” he said. “But of course, it is always more expensive.”

‘Fly carbon neutral’

Developers of projects used by airlines submit them for audits and checks by Verra and independent third parties. But they do not have to check if their predictions about the threat of deforestation—the basis the carbon credits they sell—turn out to be true.

To find out whether future deforestation forecasts were accurate, SourceMaterial, Unearthed and The Guardian commissioned new satellite analysis.

The results were stark. Analysis of four projects backed by the airlines British Airways, easyJet, and United found no evidence that the predicted deforestation had materialised.

In response to questions, the developers argued that the reason predictions of severe forest loss had not come to pass because of their projects’ role in reducing deforestation in their surrounding areas.

“Additionality is incredibly hard to prove,” said Crystal Davis, the director of Global Forest Watch. “Post-facto assessments of the integrity of baselines is really hard to do. That’s a big problem.”

‘Real-life Paddington’

Satellite analysis of an easyJet-backed project in Madre de Dios, Peru, reveals the difficulty of trying to prove the climate benefit of offsetting schemes.

To gauge prevented deforestation, developers picked a reference region nearby. But that area is far more densely populated. It encompasses the city of Iberia and is crossed by a road connecting Peru with neighbouring Brazil, making deforestation risk far higher than in the less accessible project area.

An easyJet spokesperson said that the airline “employs a rigorous process to select the schemes we buy credits from”.

North of Madre de Dios in central Peru, the Cordillera Azul national park is home to several threatened species, including the spectacled bear, otherwise known as the “real-life Paddington”. The project is central to British Airways’ claim that passengers can “fly carbon neutral” by offsetting their flight.

CIMA, the group behind the project, argued that without its intervention, immigrants moving into the surrounding area would cut down trees to farm the land, and predicted a huge increase in deforestation.

But the area was already a national park and already had protected status for seven years when it started issuing credits in 2008. “No illegal logging activities have been observed by park guards in or immediately around the project area since 2006,” CIMA wrote in 2012.

It’s unlikely Cordillera Azul would have suffered high rates of deforestation without the project, said Deyvis Huamán, a REDD+ official in Peru’s ministry for the management of protected areas.

“It’s a Pandora’s box when you do those calculations,” he said. it’s kind of arbitrary sometimes. “You put a value on the strongest driver and it might exist or it might not.”

A CIMA spokesperson said that the Peruvian government “is very pleased with the contributions made by the early initiatives working on protected areas in Cordillera Azul.”

A British Airways spokesperson said the airline aims to reach net-zero by 2050, using a range of initiatives, including carbon offsetting: “We work with our partners and project developers to choose the highest quality, independently verified projects and do due diligence to ensure they provide real carbon, economic, social and environmental benefits.”

Logging companies

More problematic, perhaps, is that the operators of the he Madre de Dios projectare two logging companies.

Maderacre and Maderyja are certified by the Forest Stewardship Council and say that they operate sustainably, exceeding requirements set by the Peruvian authorities. They argue that sustainable logging of this type can increase carbon absorption by promoting tree regeneration.

But while forestry management protects younger trees as they grow, data from Peru’s forest inspections agency show that the loggers have cut down old growth crucial to the ecosystems, including carbon-rich shihuahuaco trees and rare species like Spanish cedar and mahogany, both categorised “vulnerable” by the International Union for Conservation of Nature.

“It’s absurd” that a logging company should get paid for carbon credits as it fells shihuahuaco trees that can take 1,000 years to reach maturity, said Julia Urrunaga, director of Peru programmes at the Environmental Investigation Agency.

Like many REDD+ projects, Madre de Dios also says it supports indigenous communities who defend forests in their territories. But meeting minutes seen by SourceMaterial show that the developers opposed a government proposal to expand an indigenous reserve bordering the project in 2017. Officials feared that the isolated Mashco Piro tribe were being threatened by encroachment from outsiders. But a Madre de Dios representative argued that existing reserves were “more than sufficient” and logging concessions were a “productive conservation model”.

Project developer Greenoxx told SourceMaterial that it would welcome any decision by the authorities regarding the location of the Indigenous reserve, and noted it did not have any formal power over the decision. The NGO also highlighted its work with Indigenous communities living near the project area, claiming: “Our project is effectively contributing to the protection of their territory.”

Fig leaf

With the global offsetting market predicted to expand rapidly, airlines need to be more careful about marketing their support for offsetting projects to customers and have a better understanding of their climate impact, said Barbara Haya, a research fellow at the University of California, Berkeley.

“It’s great if companies want to support conservation projects if these actually have positive impacts,” said Gilles Dufrasne from Carbon Market Watch. “But they shouldn’t say that this compensates for their own emissions. It simply doesn’t.”

“It’s great if companies want to support conservation. But they shouldn’t say it compensates for their own emissions. It simply doesn’t.”

Even some of offsetting biggest corporate backers are sceptical. United Airlines’ chief executive, Scott Kirby, has called offsetting “a fig leaf” that allows companies to “pretend that they’ve done the right thing for sustainability when they haven’t made one bit of difference in the real world”.

A United spokesperson declined to comment on Kirby’s remarks.

Former Bank of England governor Mark Carney is leading an international task force to reform and expand the offsetting market. Its members include easyJet and Verra.

One of its challenges will be to decide whether projects like Madre de Dios represent value for money—and, more importantly, for the climate.

Additional reporting: Mitra Taj