In the dying days of the Cold War, Rainer Sonntag slipped across the Iron Curtain to become one of Germany’s leading neo-Nazis. He was also a communist spy—and worked for Vladimir Putin

With Sean Williams and The Atavist

1.

As the sun set on May 31, 1991, the streets of Dresden crackled with energy. All day the city had been abuzz with the rumour that there was going to be a riot in the city’s nascent red-light district. Since the fall of the Berlin Wall some 18 months before, the smog-choked, bomb-scarred city in East Germany had changed. Suddenly, it was filled with new imports from the West, including drugs, gambling, and prostitution. Kiosks that once sold Neues Deutschland, the dour Communist Party propaganda sheet, now carried German editions of Playboy and Hustler. One man had sworn to clean up the town. His name was Rainer Sonntag, and he was a far-right vigilante—an avowed neo-Nazi.

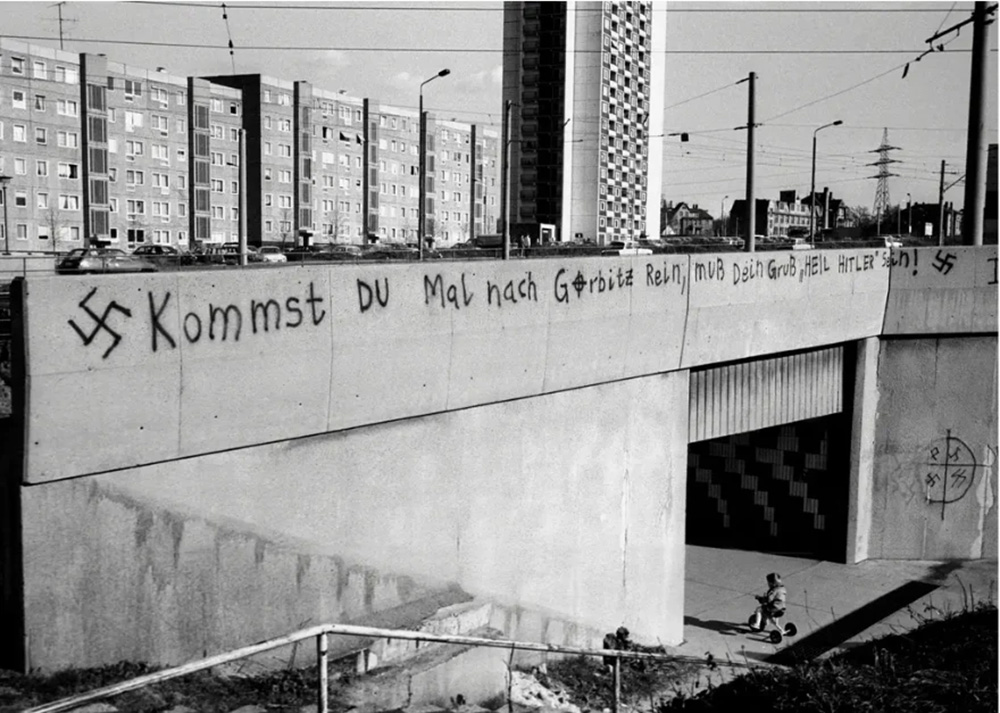

Sonntag was born and raised in Dresden, but had fled across the Iron Curtain to West Germany five years earlier. By the time the wall fell, Sonntag had become one of the West’s leading neo-Nazis, thanks to a willingness to roll up his sleeves and fight. When he returned home, he recruited a ragtag army of acolytes to rid Dresden of influences he claimed were noxious. Most of his followers came from the grim maze of housing projects in Gorbitz, on Dresden’s western edge. The buildings there were filled with young people who had been stripped of stability and purpose by communism’s implosion. Sonntag had charisma and an uncanny ability to channel the energy and anger of Gorbitz’s youth. They flocked to him, calling him the Sheriff.

Sonntag’s gang of neo-Nazis had started their supposed purification of the city by targeting the Hütchenspieler, three-card swindlers who plied their trade on Dresden’s central Prager Strasse. They handcuffed the men and handed them over to the local police. Then the youth hounded the city’s Vietnamese cigarette sellers. Now they were eyeing brothels. Never mind that not so long ago, Sonntag himself had worked in a red-light district in the West; he timed an assault on a Dresden brothel called the Sex Shopping Centre for midnight on the last day of May.

Throughout the evening, far-right youth—some with shaved heads, others with the feathery mullets still fashionable in the Eastern Bloc’s dying days—gathered in nearby bars and outside the boarded-up Faun Palace porn cinema, just down the street from the brothel. From behind the wheel of a parked car, Sonntag waited to give the signal to attack. The Sex Shopping Centre was run by a Greek pimp named Nicolas Simeonidis and his business partner, Ronny Matz.

Around 11:45 p.m., as Sonntag’s army assembled beneath the Faun Palace’s faded neon sign, Simeonidis and Matz arrived in a black Mercedes to confront them. Simeonidis, a compact amateur boxer with a 16-1 record, brandished a sawed-off shotgun. “Get out of here!” he yelled at the 40 or so young men gathered in the street. Simeonidis waved the shotgun in a wide arc, sending the neo-Nazis scattering for cover behind cars and bushes. “Leave us in peace!” he roared.

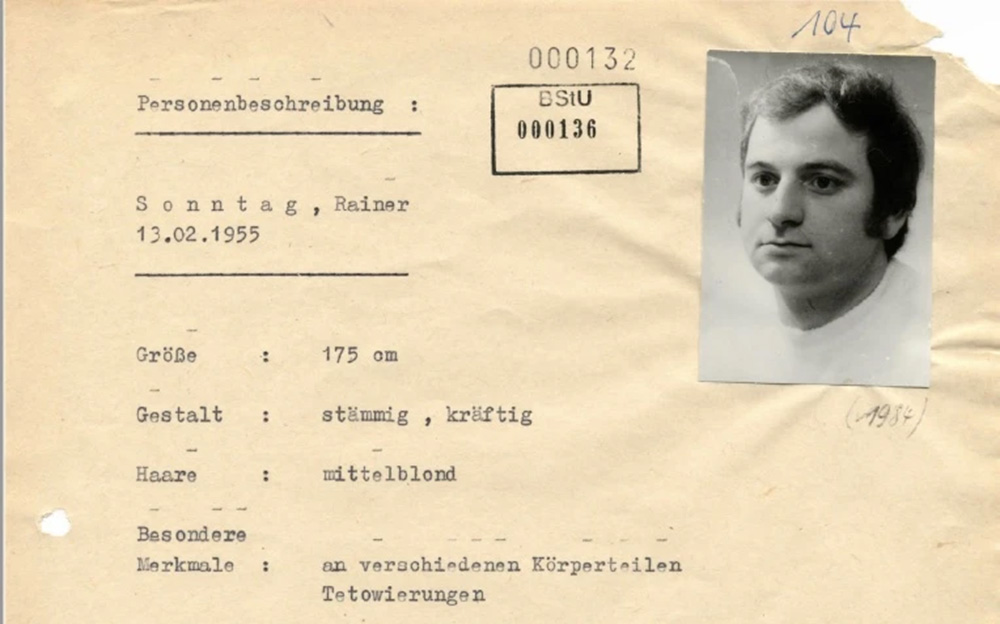

Sonntag opened his car door and emerged. He was of average height and stoutly built, with dark, wavy hair and a round, friendly face that even now seemed on the verge of breaking into an infectious smile. Sonntag had charm to spare and a vicious stubborn streak. He wasn’t likely to back down just because his target had a gun—especially not with his troops watching. “Go on, then! Shoot, you coward!” Sonntag called out, removing his jacket and advancing steadily on Simeonidis.

From their hiding places, the neo-Nazis sensed a shift in the balance of the situation. One by one, they emerged to join their leader. They were willing to follow him anywhere.

But Sonntag’s young disciples didn’t know his darkest secret. While outwardly he was a neo-Nazi, he was also a spy for K1—political police who answered to East Germany’s feared security agency, the Stasi. Not only that, he had ties to the KGB. In fact, right up until the Iron Curtain fell, one of his handlers was a young, ambitious Russian officer stationed in Dresden. The handler’s name was Vladimir Putin.

The story that follows is based on dozens of interviews with neo-Nazis, eyewitnesses, and former spies, and hundreds of pages of Stasi files and court records. It is the story of how, more than 30 years before Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine, under the disingenuous banner of “de-Nazifying” the country, he and some of his closest intelligence associates helped nourish a neo-Nazi movement across Germany. Their preferred tool was Rainer Sonntag.

2.

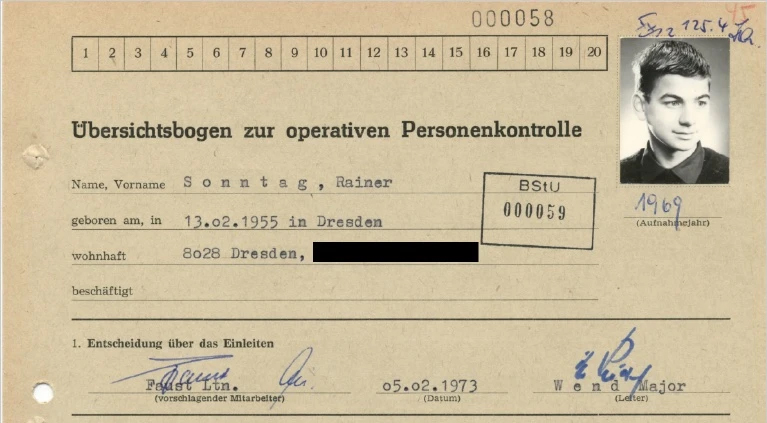

Born Rainer Mersiowsky in 1955, Sonntag never met his biological father and took his stepfather’s name. His mother struggled to keep him on the straight and narrow, and he managed to graduate high school only by repeating his penultimate year. Teachers described him as insouciant, weak-willed, and hot-tempered. He needed constant validation and lacked ambition, they said. He was repeatedly disciplined for disrupting lessons.

When he was a teenager, the Free German Youth assigned Sonntag the role of agit-propagandist; he was also a drill leader in Dresden’s Gymnastics and Sports Federation. He had an apprenticeship as a machine worker and was soon tapped to join a paratrooper regiment in the army. But Sonntag wasn’t interested in being a Communist stooge or enduring a lifetime of drudgery for a meagre wage. He began to play up. In 1972, police investigated an incident at a local ice-skating rink, where Sonntag had punched some kids in the face “without provocation”. Worse yet, as far as the authorities were concerned, he showed signs of bucking the ideological yoke. Teachers caught him singing a ribald song about the Soviet Union during a football match—a permanent black mark on his fattening police file.

By 1973, as Sonntag stared down his 18th birthday, his future looked bleak. That February, he had drinks with three friends, including a former schoolmate whom authorities referred to in official documentation as “Hans Peter”. They met at the Gasthof Wölfnitz, an old-fashioned beer hall, to discuss a daring plan: escape to the West. Like many people their age stuck behind the Iron Curtain, they dreamed of a life of freedom and material abundance, glimpsed by most East Germans only when they illegally turned their TV antennas toward the West. Around 150,000 East Germans had fled their country since the Berlin Wall was built in 1961. Many more had tried and failed.

One of Sonntag’s friends told the group at the Wölfnitz that his little brother had found a pistol in a nearby park. It was rusty and broken, but together they had cleaned and repainted it. They hoped to have it service-ready soon in case they needed it during their escape. Another of Sonntag’s friends was in a mountaineering club and had a skill set that could help them navigate the rugged terrain near the border. The young men plotted their route: first to Czechoslovakia, then to Austria, and finally to West Germany. They set a departure date for later that month, drained their beers, and headed home.

It was summer before they acted on the plan, and only Sonntag and one of his friends decided to go. In July, while Sonntag’s mother, stepfather, and brother were on holiday, he rummaged in the family’s television cabinet, looking for the envelope he knew was stashed there. When he opened it he found 350 East German marks, and a second envelope containing 120 Czechoslovakian koruna. He intended to pay his parents back once he got to West Germany and found a job.

He and his friend boarded a bus to Altenberg, a pretty, mediaeval town high in the mountains on the East Germany border with Czechoslovakia. To avoid suspicion, the young men decided to tarry for a couple of days rather than cross into the neighbouring socialist republic right away. Two days later, they woke early and changed their remaining marks into koruna. At 9:45 a.m., carrying nothing but a couple of sweaters, two knives, and his identity papers, and with money hidden in one of his shoes, Sonntag approached the border.

He and his friend were quickly separated and interrogated: what were their plans in Czechoslovakia? Sonntag told a border guard that they were headed to a parachuting competition in Prague. But his friend said they were planning to stop in Teplice, a spa town. Then the patrol found the money in Sonntag’s shoe.

Even if the friends had kept their stories straight, they never stood a chance. Their entire escape plan was already documented in a Stasi file, labelled “Machinist.” The Stasi had gathered every scrap of information they could from Sonntag’s colleagues and neighbours, the Dresden police, and a secret informant: Sonntag’s friend Hans Peter.

Sonntag and his companion were back in Dresden being interrogated by the Stasi that afternoon. “I knew I was forbidden to go to the capitalist West,” reads Sonntag’s confession, part of more than 230 pages of documentation now at the Stasi Records Archive in Berlin. “Although I knew this, I wanted to leave.” His sentence was 18 months of hard labour.

Authorities bounced Sonntag between several prisons during his sentence, including the notoriously tough Bautzen jail, a crumbling brick building known as the Yellow Misery. No matter where he was, Sonntag rebelled. He mocked the guards with his seeming obedience. “I show them a perfect cell, pretty as a picture,” he once wrote. “Three times they searched me and found nothing.” Prisoners spent much of their free time covering one another in primitive tattoos, and Sonntag, whom Stasi informants had noted possessed a talent for sketching, often came up with the designs.

In February 1974, he wrote a letter that he intended to smuggle out to his family. “The guards would love to throw me in solitary but they can’t get to me, I’ve been clever,” he wrote. Sonntag’s cockiness proved misplaced. On his way to the visiting room that month, warders frisked him and found the letter tucked in his sleeve. They punished him with three weeks in solitary.

While it is hard to know whether Sonntag began his drift to the far right while in prison, it would have been next to impossible to avoid exposure to National Socialism behind bars. The East German prison system was practically a university for Nazism; they were filled with extremists, and war criminals flaunted their radical views and groomed new recruits. According to Ingo Hasselbach, a reformed far-right activist who spent time in prison in the late 1980s, on Adolf Hitler’s birthday Nazi prisoners would paint swastikas on toilet paper and fashion them into armbands. “It may sound pathetic, but it was an incredible provocation,” Hasselbach wrote in his memoir, Führer-Ex. “Those people had a big influence on me, and on others.” Some prisoners viewed Nazism as the purest form of opposition to communism, the ideology whose agents had put them behind bars. Indeed, embracing far-right beliefs was, ironically, a demonstration of anti-authoritarianism.

For its part, the Communist Party was in denial. “Officially, in East Germany, Nazism didn’t exist,” said Bernd Wagner, a police commissioner who warned of a rising tide of neo-Nazism in 1985, only to see his report to the Politburo hushed up. His bosses’ response was as simple as it was naive: “In a socialist paradise, Nazism is impossible.”

After Sonntag was released from prison, he again clashed with authorities. They issued him an ultimatum: work as an informant for the Dresden police or go back to prison. His freedom now depended on spying on his friends. He agreed to be an informant, but became more determined than ever to get out of East Germany. Sonntag was soon plotting another break for the West.

It would be tougher this time round, not least because his criminal conviction had resulted in the police confiscating his identity papers. Crossing the border legally would be out of the question. Over beers at the Rudolf-Renner-Eck pub, he formulated a new plan: Sonntag would hide in the trunk of a car while accomplices, including a young woman with a child, distracted guards at the border between East Germany and Poland, hoping to prevent the officers from searching the vehicle. Once in Poland, they would sell the car to buy passage across the Baltic Sea and out of the Eastern Bloc. But the authorities were several steps ahead of him: This time, the young woman’s mother was the one who ratted him out.

By 1975, Sonntag was back in jail, charged with “attempted flight from the Republic”. While he was behind bars, the Dresden police continued to use him as an informant. Snitching on fellow prisoners could bring all sorts of benefits in East Germany, from cigarettes to a comfier cell to a shorter sentence. Still, it was dangerous work. The faintest whiff of suspicion could be fatal. Sonntag took the risk anyway. When he was released after three and a half years, it didn’t take long for him to be arrested once more, again for theft. He got out two years later, in 1981, this time for good.

Sonntag had little to show for himself, and his dream of escaping to West Germany seemed more distant than ever. But things were starting to change in the East. For years the authorities had ransomed prisoners and criminals to the West as a way of raising hard currency. In the early 1980s, they expanded the practice, and thousands of East Germans began applying to leave. In theory, leaders in West Germany were paying for political dissidents of conscience; in practice, they never knew who would be shipped over. “East Germany palms its neo-Nazis off on us,” one West German politician complained to the newspaper Die Zeit in 1989.

The authorities turned down far more ransom applications than they approved, but Sonntag had little to lose. In 1984, he put in his official request. If he had ties to the far right at the time, which seems likely given his numerous prison sentences, he kept it under wraps. He told his drinking partners that if he was allowed to leave, he would join the West German army or find work as a private detective.

As ever, the Stasi was listening. In one of the police state’s many paradoxes, “people who asked to leave were, unsurprisingly, suspected of wanting to leave,” writes Anna Funder in Stasiland. In other words, the requests were legal, but the authorities could also choose to view them as a smear against the state. Based on his ransom application, Sonntag was immediately placed under investigation.

Apparatchiks drafted a 16-point operational plan to preempt the escape plan they were sure Sonntag would hatch if his application was rejected. The Stasi’s ubiquitous network of code-named snitches—Peter, Berger, Nitsche, Pilot, Sander, Roland, Eberhard, Brinkmann—monitored Sonntag’s every move. They followed him to his job packing goods, sat across the room at his favourite watering holes, and even hid outside his apartment.

More often than not, they turned up intelligence that was painfully banal. “On October 6 I could confirm Sonntag and his girlfriend were in his flat,” reads a typical report from an informant with the code name Goldbach. “From voices in the corridor, and lights on in the kitchen and living room, I concluded that both people were at home. The extent to which other people were present I was unable to establish. It seemed to me however, that there were several women in the flat. I didn’t get the impression that anybody planned to leave the place in the evening.”

Behind the dull bureaucracy of police surveillance, however, more powerful forces were at work.

3.

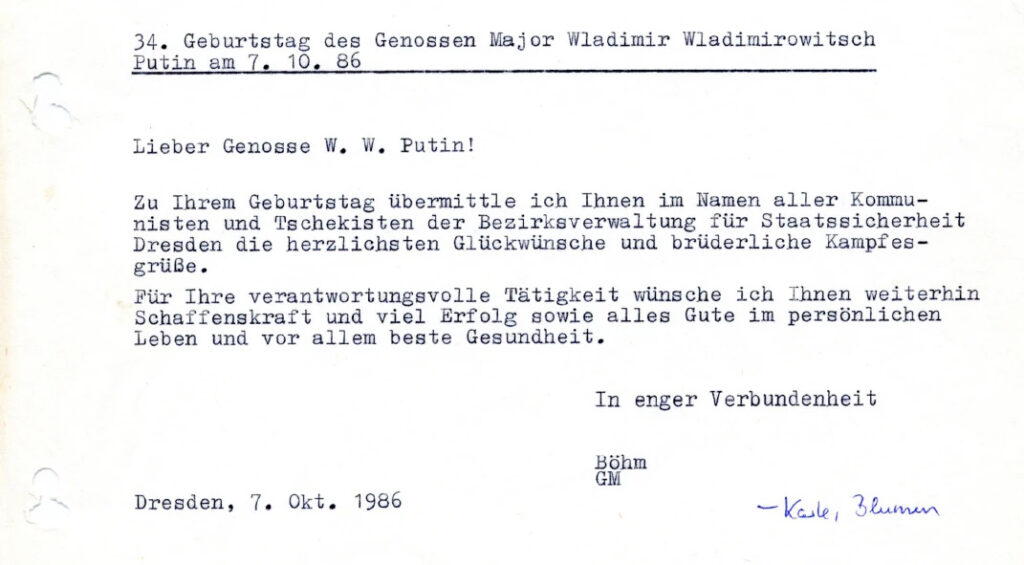

Klaus Zuchold never called the short, blond-haired deputy at the KGB’s Dresden headquarters Comrade Putin. He was always Volodya: “Little Vladimir.”

Zuchold was a 28-year-old trainee spy handler when he first met Putin, at an early-morning football match organised by the Stasi in September 1985. Putin, 32, was a gifted sportsman who played striker. Like most spies of the era, he had an official cover: He was stationed in Dresden as a diplomatic translator, even though his German was rudimentary. He and Zuchold spoke Russian when they met.

Putin had arrived in Dresden from Leningrad a month before, followed by his wife and baby daughter. In the Soviet Union, he had worked in the KGB’s Fifth Directorate, the division tasked with fighting “ideological subversion” by using informants and agents to flush out anti-regime agitators and pamphleteers. Now Putin lived in a three-room apartment a few minutes by foot from the KGB’s modest Dresden headquarters, a suburban villa on the leafy Angelikastrasse.

The mid-80s were a tough time in the Soviet Union. New premier Mikhail Gorbachev had just announced his perestroika reforms to counter shortages and long lines for food. But in East Germany, “there was always plenty of everything”—especially beer, Putin told the authors of First Person, a biography published in 2000. He often took intelligence contacts to pubs and breweries. He would later claim that he gained 25 pounds during the posting.

Berlin, the undisputed capital of Cold War espionage, lay 100 miles north. Dresden, by comparison, could seem like a backwater. The KGB had only six agents working out of the Angelikastrasse office, but they were busy. The city was a hub for contraband—diamonds, antiquities, and weapons, sales of which helped sustain sclerotic socialist economies. It was also home to Robotron, East Germany’s largest computer manufacturer, which owed its success to the theft of intellectual property from Western tech giants, including IBM.

The KGB’s biggest task in Dresden was to recruit agents from among the city’s left-leaning students, scientists, and businesspeople, who for one reason or another felt disenchanted with the West. Putin “knew how to be polite, friendly, helpful, and unobtrusive,” wrote a spy who published a book under the alias Vladimir Usoltsev. He shared a desk with Putin in the Angelikastrasse villa’s attic. “He was able to win over anyone,” Usoltsev wrote, “but men old enough to be his father were his forte.” Putin was no ideologue, according to Usoltsev: he could play-act a convincing communist, but in reality he was “a pragmatist, somebody who thinks one thing and says another.” Anything was on the table so long as it meant destroying his enemies.

Putin was soon promoted, becoming the KGB’s direct liaison with the Stasi, whose offices and prison in Dresden occupied a vast former paper mill. He also led a crack team comprising KGB operatives and members of the police force’s feared K1 division, which was responsible for rooting out citizens with a “hostile-negative orientation” and keeping tabs on people suspected of wanting to flee to the West. At any time, K1 had about 15,000 informants on its roster. Combined with the Stasi’s inoffizielle Mitarbeiter, or IMs, East German security agencies had more than 200,000 informants—one for every 63 citizens. “Everyone was followed,” Putin says in First Person. “Of course that wasn’t normal. It wasn’t natural.”

The relationship between the KGB, Stasi, and K1 was a complicated one. Technically, K1 was an arm of East Germany’s police force and overseen by the Ministry of Interior. It was the Stasi, however, that called the shots, and not everyone in the Stasi was happy that a KGB officer had control over a K1 team. The Soviets were allies, but they were also occupiers—many East Germans remembered the brutality of the Soviet advance into their country in 1945.

Still, while the KGB and Stasi were far from friendly, they were brother agencies, and now that Putin had ascended the intelligence ranks, he had his own Stasi ID card and could come and go from the bureau’s Bautzner Strasse headquarters as he pleased. He was assigned a right-hand man named Georg Johannes Schneider, a K1 officer and former Dresden policeman with tan skin and close-cropped hair, who enjoyed hunting and restored old furniture for the large apartment he shared with his journalist wife.

It was Schneider who pulled in Klaus Zuchold to help the KGB recruit agents in Dresden. The two men first met at an event for law enforcement officers 17 miles south-east of the city, where Saxon forests fold into spectacular sandstone peaks along the Czech border. Almost everyone had gone to bed when Schneider approached Zuchold, a Stasi officer working under the alias Frank Wollweber, and raised his glass. “Prost Aufklärung,” Schneider toasted, according to a 2015 report by Correctiv, a German nonprofit newsroom. To espionage.

It was an indiscreet opening gambit, to say the least. With those two words Schneider outed himself as a shadow operator for the KGB. But Zuchold didn’t balk. The pair drank and agreed to meet again. Before long Zuchold was working surreptitiously alongside Schneider and Putin. When his Stasi bosses discovered that he’d been meeting with a KGB officer, they reassigned him, hoping to limit his access to information that might interest the Soviet Union.

Even still, Zuchold proved useful. Together he, Putin, and Schneider established a network of around 20 KGB assets, some of whom were paid a monthly stipend of as little as 50 East German marks—$38 today—to provide intelligence. Their recruits were mostly Dresden locals with contacts in the West. Zuchold’s operatives included a female journalist with an array of international connections, and a man he wouldn’t name who he said is now a senior German judge.

Zuchold was good at his job, but Schneider was better. He was a maverick with little respect for the rules and the kind of energy and charisma that easily won over potential collaborators. One of his biggest coups was the establishment of a pipeline through which German-speaking Latin Americans, recruited as KGB agents, were funnelled to West Germany.

Schneider took to wearing safari suits and dark glasses. “He looked like a mafioso,” Zuchold said. He was also good company: “He’d entertain everybody. And the people would all be taken with the man.” But Schneider had a dark side. Though married to a pretty redhead—whom Zuchold was sure Putin was jealous of—Schneider was a predatory womaniser. He slept with agents as well as the wives and girlfriends of his colleagues. He was rumoured to have raped the 10-year-old daughter of an informant, though charges were never brought.

Thanks in no small part to Schneider’s recruitment efforts, Putin prospered, winning two more KGB promotions in short order. “All the success that Putin had in Dresden was first and foremost because of Schneider,” Zuchold said. Schneider was the person who came up with the idea of transforming Rainer Sonntag from a low-rung police informant into something else entirely.

As a Dresden policeman, it was Schneider who recruited Sonntag. (Their relationship was first reported by Correctiv.) Sonntag had since become an ardent right-winger—one IM claimed that he had a side hustle selling Nazi memorabilia on the black market. When Sonntag’s request to be ransomed to the West landed on Schneider’s desk, he saw an opportunity: what if the East Germans—and by extension, thanks to Putin’s role in Dresden, the KGB—planted Sonntag as an active informant on the other side of the Berlin Wall?

At its peak in the late 1970s, the Stasi had more than 200,000 IMs on its books—one for every 63 citizens. “Everyone was followed,” Putin said.

The Stasi had a rich history of exploiting the far right for its own ends. When Adolf Eichmann stood trial in Jerusalem, the Stasi funnelled cash to a campaign to defend the captured war criminal and forged letters from “veterans of the Waffen-SS” urging comrades to join the “struggle against Jewish Bolshevism,” all in an effort to humiliate the West German government. With the same goal in mind, in the late 50s and early 60s, Stasi agents smeared swastikas on Jewish graves across the country. Later, in the 1980s, the Stasi recruited Odfried Hepp, one of West Germany’s most wanted neo-Nazi terrorists, to report on far-right activity on his side of the Berlin Wall. When it appeared that Hepp’s arrest was imminent, he fled to East Germany and was smuggled to Syria under a new identity.

Author Regine Igel, who has studied extremism in modern Germany, believes that the East German intelligence apparatus was engaged in “massive and long-term support and direction of German and international terrorism,” exploiting extremists on both right and left to destabilise the West. By Sonntag’s time, however, the authorities’ approach to the far right may have become more pragmatic, concerned with heading off neo-Nazi attacks against border installations and countering the spread of the ideology in East Germany. “Following the logic of ‘my enemy’s enemy is my friend,’ there was a basis for cooperation,” according to historian Bernhard Blumenau. “This was realpolitik at its best.”

Unleashing Sonntag in West Germany was a gamble. He was a loner, with few personal relationships to ground him. There was a good chance that, once free, he would simply vanish. But he was about to surprise his handlers.

When Sonntag applied to go to the West in 1986, it was Vladimir Putin who approved the request.

4.

When Sonntag arrived in West Germany in 1986, his first stop was Giessen, a refugee camp north of Frankfurt. There he boasted that he’d been “bought free,” or ransomed as a prisoner of conscience. Staying at Giessen meant routine questioning by West German intelligence officers, and possibly by their British, American, and French allies. He must have hidden his connection to Schneider and Putin well enough: Authorities quickly cleared him to leave Giessen and build a life in West Germany.

Before long, Sonntag gravitated toward Frankfurt’s underworld. With his prison record and quick fists, he blended in to the scene. He got work as a brothel doorman—a “slut minder,” as he liked to call himself. He even landed in court for weapons possession and assault. (The details of the crime have been lost; court records from the era were routinely destroyed.)

As Sonntag established himself among criminal elements in the West, he reported back to Schneider and Putin. It’s not clear how they kept in touch, according to Zuchold, but Stasi operational practice at the time would have allowed for a number of options. One was to meet in “socialist abroad” countries—states friendly to East Germany, such as Czechoslovakia and Hungary. Another common method was to rendezvous in Stasi-monitored service stations along the autobahn that connected East Germany to West Berlin. At least initially Sonntag was a low-grade informant, not someone to be trusted with courier duties or equipped with a clandestine radio. Nor was he worth the risk of his handlers crossing into the West to meet him.

That changed in 1988, when Sonntag caught the eye of West Germany’s most powerful neo-Nazi. The self-styled führer of the coming Fourth Reich, his name was Michael Kühnen. While Sonntag was a blue-collar rabble-rouser, Kühnen was a lean former soldier with a military bearing, sculpted cheekbones, and fastidiously pressed uniforms. He looked straight out of a Nazi propaganda movie. Kühnen was also a sophisticated strategist and provocateur. In May 1978, he and his neo-Nazi troops marched through Hamburg’s city centre wearing donkey masks and placards around their necks declaring, “I’m a jackass who still believes that Jews were gassed in German concentration camps”.

Like Hitler, Kühnen wanted to gain power through legitimate elections. He and his followers started one political party after another, including the National Assembly, the National List, the National Alternative, the German Alternative, and the Covenant of the New Front. The complex network of entities flummoxed both academics and antifascist activists, but the organising principle was simple enough: Whenever the government banned one of his political parties, Kühnen formed another one. “We didn’t found one great political organisation but a lot of smaller ones, because it’s harder to ban all of them,” said Christian Worch, who served as Kühnen’s chief of staff in the 1980s and remains deep in the neo-Nazi movement today. This presented West German authorities with an endless game of Whac-a-Mole.

Behind the political front groups was a backdrop of terror. The violence had begun in 1970, when a Russian soldier standing guard at the Soviet war memorial in West Berlin’s Tiergarten was shot and wounded—the first in a series of increasingly grisly far-right attacks that, within a few years, escalated into bank robberies and bombings. In 1979, three neo-Nazis were arrested for planning an assault on a West German communist group’s offices. One of the men had stolen a large quantity of sodium cyanide. He had planned to poison the guards at Berlin’s Spandau Prison and free its only prisoner, the Nazi war criminal Rudolf Hess.

The same year, Kühnen received a three-and-a-half-year prison sentence for inciting violence and racial hatred. While he was behind bars, the wave of brutality he helped unleash culminated in one of Germany’s worst peacetime atrocities: On September 26, 1980, a pipe bomb stashed inside a trash can at Munich’s Oktoberfest exploded, killing 13 and injuring more than 200. Three months later, a Jewish community leader and his partner were shot dead at their home. In 1981, security forces hunting the neo-Nazi gangs responsible for these crimes uncovered the biggest weapons cache ever found in postwar Germany: buried in a forest in Lower Saxony were 88 crates containing 50 Panzerfaust anti-tank weapons, 14 firearms, 258 hand grenades, more than 300 pounds of explosives, and 13,500 rounds of ammunition.

Once freed from prison, Kühnen set up his headquarters in Langen, a town south of Frankfurt with pretty half-timbered houses huddled around a mediaeval square, like something out of a children’s picture book. A few blocks away, on the Strasse der Deutschen Einheit, was an altogether different building, a modernist complex built in the late-1950s to house East Germans who had fled communism. It had since become home to refugees from all over the Eastern Bloc who were waiting to secure steady work and permanent housing. As bureaucracy slowed their relocation process and the complex became overcrowded, residents turned their anger toward local immigrants from the Middle East and Africa, many of whom had fled political violence or poverty to build new lives in Germany. “Just look how these asylum seekers live,” said a leader of the Federation of Expellees, a right-wing support group for Germans who had lost Eastern European property in World War II. “They all have the biggest TV sets, a video recorder, a car.”

That animosity helped make Langen the unofficial capital of West Germany’s rapidly swelling neo-Nazi movement. Far-right activists, including Kühnen, enlisted skinhead gangs to distribute racist flyers outside schools and stake out parks and playgrounds, beating up people of colour who dared to use them. Their aim was to make Langen ausländerfrei, or “foreigner free,” something that would be far easier to do in a small town like Langen than in one of West Germany’s larger cities. “20 men in Langen are worth 200, 300, or 400 in Frankfurt,” Worch said.

By 1988, Kühnen needed people around him he could trust. Two years before, he had come out as gay, writing that “the sexual relations between men that arise from friendship and love and the deepening of devotion to the fellowship can never harm that fellowship.” Kühnen’s sexual identity had long been the stuff of rumour, but he had been forced to play his hand after he was diagnosed with HIV. As other neo-Nazis began to circle, looking to use his status as an excuse to push him from their movement’s ignominious throne, Kühnen made sure his inner circle was tight and full of proven friends.

Among them was Sonntag. It’s not clear when or how the two men met, but once they did, according to Worch, Sonntag quickly became Kühnen’s sergeant at arms. In practice this meant that he was the personal bodyguard and head of security to the most powerful neo-Nazi leader in West Germany. He was an enforcer, tasked with rooting out spies and traitors.

Sonntag also formed and commanded a platoon of hand-picked street fighters who waged running battles with left-wing gangs on the streets of Langen and Frankfurt. When the neo-Nazis attacked, Sonntag led by example. At protests, often under the gaze of the police, he fought with his fists. When he and other men guarded far-right activists distributing racist leaflets, he carried a club. Sonntag also sought opportunities to go on the offensive. Worch recalled driving him around Frankfurt to hunt down anarchists and punks. “Sonntag was always in the front line,” he said.

It was also Sonntag who dealt with the press—a responsibility that gave him control of one of the neo-Nazis’ few sources of income. Newspapers paid 550 marks for interviews ($660 in today’s dollars), while camera crews paid 950 marks ($1,280). A French TV team put up 2,000 francs ($800) for an election exclusive, and when the Nazis drove to an out-of-town rally, a Danish broadcaster bought the gasoline.

As Kühnen’s health declined, Sonntag’s prominence in the neo-Nazi movement rose even further. “Suddenly, he was the chief,” Zuchold said. “Kühnen was sick with AIDS, and Sonntag was next in line.” This made some within the neo-Nazi movement nervous. Sonntag “was not easy to trust,” said Ingo Hasselbach, adding that Sonntag’s work as a pimp was beyond the pale for many of his comrades. “We kept warning Kühnen. We said, ‘Something’s wrong with this guy.’ ”

But Sonntag’s fortune was a stroke of luck for Schneider and Putin. Available documentation doesn’t specify the information Sonntag provided his handlers, but what both the East Germans and KGB wanted most was influence and a direct line to people in power. The Stasi’s most famous coup in this regard had been to recruit Günter Guillame, a personal assistant to West German chancellor Willy Brandt, who resigned in 1974 after the agent was exposed. By the late 1980s, it was clear that neo-Nazis were emerging as a powerful political force. Sonntag, situated tantalisingly near its apex, was an invaluable asset to the prying forces of the East.

By early 1989, riding the tide of xenophobia in Langen, the city’s neo-Nazis had easily acquired the number of signatures needed to run their National Assembly party in a local election, with Sonntag as a leading candidate. Victory would have been a major step toward making Langen ausländerfrei. But then the West German authorities stepped in: They banned the party from the elections and raided senior leader Heinz Reisz’s home, seizing his favourite Hitler portrait live on national television.

As ever, the neo-Nazis regrouped. That November the Berlin Wall fell. While much of the world celebrated, and East Germans revelled in the newfound capitalist plenty of supermarkets and shopping malls, Kühnen’s men in Langen sensed an opportunity. What if they staged a far-right revolution in the GDR? People in the East were suddenly unmoored. National Socialism, with its vociferous rejection of the past half-century of Communist rule, could be their new anchor.

In some ways the neo-Nazis had already laid the groundwork. A flurry of groups had been created as cover for the banned National Assembly party. One of them, Deutsche Alternative, would provide the fig leaf needed to kick-start a political uprising in the East. “A party program will be formulated for the DA in Middle Germany in such a way as to allow it to be legally registered,” read the road map for revolution, referred to as Arbeitsplan Ost, or Workplan East. The next step was to win new supporters. Each Monday, up to half a million protesters filled a church square in Leipzig, East Germany’s second-largest city, to protest the lingering Communist regime. As peaceful protest spread across the crumbling GDR, the neo-Nazis wanted to nudge the participants—and thus the entire country—toward political extremism. By planting activists among the crowd, they planned to provoke a shift toward racism and xenophobia. “Our activists will take part in demonstrations and attempt to radicalise them,” the Arbeitsplan Ost document read.

But a neo-Nazi leader named Gerald Hess was worried the plan might fail, due to sabotage. He was convinced that someone within the movement’s leadership was leaking information about Arbeitsplan Ost to government authorities. At first, Hess’s suspicions fell on a filmmaker named Michael Schmidt, who only recently had become close to Kühnen. Hess and Schmidt were friendly. The filmmaker had even attended a home screening of a 1940 Nazi propaganda film depicting Jews as rats ravaging Europe with disease. But Hess was becoming increasingly paranoid.

In the summer of 1990, Hess invited Schmidt to have a beer and confronted him. “You know I like you,” Hess said. “But I don’t trust you anymore. Are you with the filth?” Schmidt talked Hess down, assuring him he wasn’t a traitor, but that only meant Hess’s suspicions needed to fall on someone else.

He turned his attention to Sonntag, who was also relatively new to the neo-Nazis’ ranks in West Germany. But Hess would never get the chance to confront Sonntag: Five days after his meeting with Schmidt, Hess was found dead in his bedroom, his chest blown apart by a shotgun. “Here in Langen, many believe that you shot Gerald,” Kühnen wrote to Sonntag in a letter dated August 24, 1990. “The circumstances are mysterious. Some point to suicide, others to murder.”

Hess’s death may have cast suspicion on Sonntag, but that mattered less than his utility. He soon returned to his birthplace. According to the Langen rumour mill, he brought along a shotgun and 6,000 marks stolen from Hess. With his intimate knowledge of Dresden’s drinking halls, alleys, and slums, he was the perfect man to put Arbeitsplan Ost into action. Soon he was leading the effort to establish an array of Kühnen-linked parties in the former GDR: National Resistance, Schutzstaffel-Ost, and the Band of Saxon Werewolves.

But before that, Sonntag made contact with his East German handler. In fact, it was the first thing he did when he returned home. When he arrived at a border crossing between West German Bavaria and East German Thuringia, he told the guards to summon Georg Johannes Schneider. Sonntag refused to deal with anyone else.

5.

Putin was gone by then. After heaping piles of KGB files into a furnace as an anti-Communist mob bore down on his office in Angelikastrasse, he returned home to the Soviet Union as the East German security apparatus collapsed. The vast majority of K1 and Stasi informants simply stopped being on the payroll overnight. But the lights at the Stasi’s Berlin headquarters, a sprawling forbidden city left blank on city maps, remained on for two days. When citizens stormed the complex, they realised why: Stasi agents had been destroying files around the clock—beginning with those of Westerners they had recruited as spies. In one building alone, there were over a hundred shredding machines.

The collapse of East German intelligence left Schneider where he had started: with the Dresden police. There he headed a department charged with tackling left- and right-wing extremism on Dresden’s increasingly unruly streets. Sonntag, newly returned, proved a great weapon “for stirring up trouble,” Schneider told Zuchold when the two men met for a drink in 1991. Zuchold had been sentenced to three years in prison in 1988, after East German officials discovered his unauthorised shadow work for the KGB. He was released when the wall fell and quickly recruited by German intelligence to spy on Schneider and Putin. (Zuchold alleges that the two men met several times between 1991 and 1993.)

In one encounter, Schneider told Zuchold that he was using Sonntag to play the city’s neo-Nazis off its punks and anarchists. Putin’s former right-hand man explained that he used neo-fascists to keep the left in check, and vice versa. He didn’t want either side to control the streets; chaos was his preferred state. This meant that when Sonntag’s gang stalked Dresden, the police often looked the other way—and in some cases actively helped them. On one occasion, a police officer used his private vehicle to give Sonntag a ride to a neo-Nazi operation.

Sonntag’s attention was focused on Gorbitz, where he knew he would find like-minded individuals. On an underpass marking the neighbourhood’s boundary was a spray-painted slogan alerting visitors that a “Heil Hitler” salute was the expected greeting. The message was flanked by swastikas. The pale youths who roamed Gorbitz’s monochrome streets were often armed with baseball bats, chains, and knuckle dusters. They were lost, in the words of one police psychologist, amid an “existential economic, psycho-social, and political adjustment.” In East Germany’s industrial heartland, state businesses had collapsed, and reunification was doing nothing to curb soaring unemployment.

As the cold paternal hand of the state withdrew, disillusioned youth drifted through Gorbitz’s grey labyrinth toward its grim focal point, a slab-built pub called the Grüner Heinrich. That’s where Sonntag, now 35, set up shop in 1990. He was always accompanied by his beloved German shepherd.

Kühnen had envisioned Sonntag’s homecoming as a keystone of Arbeitsplan Ost. But Sonntag moulded a different reality. Gorbitz’s 35,000 residents had been born into a one-party state. Now they were gleefully ripping up their party cards; they hardly wanted to join a new one, not even Deutsche Alternative. What they did want was an outlet for their pent-up frustrations. Sonntag invited youth to Friday “Comrade Evenings” at the Grüner Heinrich, then marshalled them into bands that harried small-time criminals and foreigners. “I don’t have anything against foreigners,” Sonntag once told a local social worker named Hussein Jinah. “I just don’t want them here.”

The violence mounted as the number of Sonntag’s followers grew. In the early hours of Easter Sunday 1991, a young Mozambican slaughterhouse worker named Jorge Gomondai—one of 90,000 foreign contract workers who lived in special housing set apart from the city’s native population—was thrown from a streetcar by a gang of neo-Nazi youth. “It was a matter of life and death,” said Jinah, whose own immigrant status made him a target. “You heard these horror stories all the time.”

Around 7,000 Dresdeners attended Gomondai’s memorial service, but their concern was not enough to stem the rising tide of far-right activism and violence. In short order, Sonntag’s recruitment and provocations had made the city Germany’s new capital of neo-Nazism, and had earned him the nickname Sheriff of Dresden. Soon extremists from all over the country were visiting.

The extent of Sonntag’s success was most apparent when a film crew waited at Dresden’s central train station to capture the arrival of the führer himself: Michael Kühnen. Footage captured that day shows Kühnen on the concourse, surrounded by apathetic policemen and flanked by his most loyal lieutenants, including a smirking Sonntag, as the crowd chants, “Deutschland den Deutschen, Ausländer raus!”—“Germany for the Germans, foreigners out!”

Sonntag’s recruitment and provocations had made the city Germany’s new capital of neo-Nazism and earned him the nickname Sheriff of Dresden.

As Sonntag amassed power, Schneider worried that his asset was running wild. According to Zuchold, Sonntag “became gradually ill-disciplined and began to be uncontrollable.” In April 1991, Kühnen died from complications of AIDS, leaving Sonntag as one of the most powerful neo-Nazis in Germany. By then he had already set his sights on Dresden’s sex industry, which was sweeping into his hometown from the West. “Dresden must not become Frankfurt,” Sonntag told his street troops, who put local cathouses, including the Sex Shopping Centre, under surveillance. “The brothels must be destroyed.”

The reality of the situation may have been somewhat different than the rhetoric. Sonntag had brought his underworld experience to vigilantism: When his gangs attacked the cigarette merchants, for instance, they stole the men’s wares to sell themselves, and rumour had it that the real reason Sonntag targeted the brothel was that the pimps had failed to pay him protection money.

On the night of May 31, Sonntag and his gang prepared to smash up the Sex Shopping Centre. When Nicolas Simeonidis pulled out his shotgun, Sonntag didn’t hesitate to advance. Some people later said that he had a knife on him. Armed or not, Sonntag kept coming, arms raised, daring the brothel owner to fire at him. Simeonidis slowly backed away until he was up against his own car. He felt behind him cautiously, without taking his eyes off Sonntag, and lowered himself carefully into the passenger seat.

“Come on, shoot! You don’t have the balls!” Sonntag goaded.

As Simeonidis attempted to pull the car door shut, Sonntag jammed it open with his powerful grip. For a split second they remained locked in their positions. Then Ronny Matz, Simeonidis’s business partner, reached across the car’s interior from the driver’s seat and unloaded pepper spray in Sonntag’s face. From inside the cloud, a single gunshot rang out.

Matz stamped on the accelerator, and the Mercedes streaked away. Sonntag lay on the ground in a slowly spreading pool of blood, the left side of his head blown away.

6.

When Sonntag died, Schneider told Zuchold it was “best for everyone.” But in truth perhaps the only thing more terrible than Sonntag’s life was his death. He immediately became a martyr to the neo-Nazi movement, and his followers took out their rage on Dresden. First they rampaged through the Sex Shopping Centre, making good on their vow to destroy it. Then, in the days, weeks, and months that followed, they unleashed terror on the city at large.

Skinheads ransacked stores and attacked anybody they deemed foreign. Police showed up late to fights and crime scenes, or not at all. “Those of us with different skin colour wouldn’t head out on the street after 6 p.m.,” Jinah said. “When the sun went down, we became afraid.” Gangs attacked him twice, Jinah said, and he barely managed to escape.

Nick Greger, who was 15 at the time, was inspired to run away from his home in Bavaria to join the nightly violence in Dresden. “It was very terrible,” said Greger, now a reformed extremist. “Our shoelaces were white, for white power, and I woke up one day and they were red. I thought, ‘Oh no no, I killed somebody.’ ” Another young neo-Nazi, a roofer named Sebastian Räbiger, set up a vigil for Sonntag outside the Sex Shopping Centre. He would go on to become a leader of a German hate group called the Viking Youth and inculcate a new generation of neo-Nazis.

Soon the violence had spread to Hoyerswerda, a town 35 miles northeast of Dresden. There, rioting skinheads tossed Molotov cocktails into asylum seekers’ homes in September 1991. The same year, Hoyerswerda became the first German town to be declared ausländerfrei. Where they had failed in the West, the neo-Nazis were succeeding in the East.

Like Horst Wessel, the 1930s thug lionised by Hitler, Sonntag became a martyr. His memorial procession, held two weeks after his death, was reportedly the largest gathering of neo-Nazis since the end of World War II. A crowd of more than 2,000 people walked beneath overcast skies, making their way toward the towering neo-Renaissance building that housed Dresden’s courts. They were accompanied by the heavy beat of drums and grew rowdier as they approached the courthouse steps. Many of the mourners were raised in the Communist wastelands of suburban East Germany and had come to pay tribute to a man they saw as a hero who promised a future free from poverty, crime, and disorder—only to be cut down in his prime. “He was no ordinary person,” a man with a megaphone cried. “He wasn’t one of many. He was a comrade to his comrades, a master to his followers, an outstanding campaigner for our shared ideals.”

The crowd raised their right arms, with three fingers outstretched to make the W for widerstand—resistance.

“Rainer Sonntag is dead,” the man continued, “but Germany lives.”

The mob roared. “Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil! Sieg Heil!”

It wasn’t the last time Sonntag’s supporters would rally. In March 1992, Simeonidis and Matz were acquitted of killing the Sheriff of Dresden; a court ruled that they had acted in self-defence. Neo-Nazis rioted in response. The acquittal was overturned on appeal, and both defendants served time.

All told, the dynamics of Sonntag’s death couldn’t have been better suited to far-right propaganda. “We always had this picture of foreigners as dangerous, killing Germans, and now we have this guy shot by Greeks,” said Ingo Hasselbach, the former neo-Nazi. “It just fit into the picture.”

A few years after the Iron Curtain fell, Schneider was arrested for collusion with Moscow, on the basis of intelligence gathered by Zuchold. He was fired from the Dresden police and worked as a private detective until 1999, when a group of men entered his apartment and beat him with an iron bar. Zuchold suspected some of the criminals Schneider had befriended as an agent turned on him. Schneider spent two days in a coma. After he woke up, he was never the same. “The man was unrecognisable,” Zuchold said. “When I had a conversation with him, sometimes he laughed, then he cried. There was really severe damage.” Schneider spent the next decade drinking at a local Irish bar and died, at the age of 62, in 2010.

Zuchold reinvented himself—first as a hotel receptionist, later as a security consultant. In 2017, he claimed that he was the target of an assassination attempt while on a train from Fulda to Leipzig. “At around 11 a.m. I was jostled from behind by an unknown man,” Zuchold recalled, with an intelligence officer’s regard for detail. “During that contact, he pushed a sharp object into my upper left arm. He said, ‘Excuse me,’ and exited the compartment in the direction of the front of the train.” Fatigue set in almost instantly, and Zuchold’s arm began to swell. A week later he was admitted to the hospital. Doctors operated for hours to address the swelling; after inconclusive lab results, they deemed it a “suspected abscess,” though similar tactics have been used by Russian operatives looking to eliminate enemies of Russia—and more specifically of Vladimir Putin.

If there is a winner in this whole sordid story it is Putin, now one of the most powerful men in the world. Since assuming the Russian presidency for the first time in 2000, he has distilled his nation’s fledgling democracy into an autocracy, murdering rival politicians and journalists and replacing them with oligarchs and a ruthless propaganda machine. Along the way, he has repeatedly instrumentalised the far right to his advantage. “Putin was never a good Communist,” said Anton Shekhovtsov, author of Russia and the Western Far Right. “It was the service to the state that was the most important thing.”

Putin has invigorated the far right at home. He has ridden with the Night Wolves, an ultra-conservative biker gang, and created a national movement called Nashi—“Ours”—that enlisted football-gang members allied with Russia’s neo-Nazi underground. He has also built alliances with neo-fascist leaders across Europe. Marine Le Pen, leader of France’s right-wing National Rally, borrowed roughly $11 million from Russia to fund her party’s quest for power. Italian Lega leader Matteo Salvini, who posed in a Putin T-shirt in Moscow’s Red Square, has called the Russian leader “the best statesman currently on earth” and has also sought funding from Moscow. As of this writing, populist leaders in Budapest and Belgrade continue to appease Putin as Russian tanks roll across Ukraine.

Putin’s influence can also be felt in present-day Germany, where the Kremlin has forged ties with members of the Alternative für Deutschland, a national political party espousing anti-Semitism and racism so virulent it has been placed under the official watch of domestic intelligence. The AfD’s heartland is in Saxony, the region encompassing Dresden. It has remained a stronghold of the German far right since Sonntag’s day.

In 2014, the city gave birth to the anti-immigrant group Pegida (Patriotic Europeans Against the Islamicization of the Occident). In 2019, city authorities declared a “Nazi emergency.” The following year, German president Frank-Walter Steinmeier warned that a ceremony to mark the 75th anniversary of Dresden’s obliteration by British bombs risked becoming a rally for the far right. Steinmeier was right: In 2022, as dignitaries gathered in a cemetery to commemorate the bombing, some 750 neo-Nazis marched through the city centre with loudspeakers blaring Richard Wagner, Hitler’s favourite composer.

Germany’s far right shows no sign of waning. “The scene will get bigger, in fine garb, and in the guise of neoconservative political parties,” Zuchold predicted. In a sense, Arbeitsplan Ost continues. This is the ugly legacy of Rainer Sonntag and his handlers.

With assistance from Marlene Obst